Monique Meloche Gallery is pleased to present Antonius-Tín Bui’s second solo exhibition:

There are many ways to hold water

without being called a vase

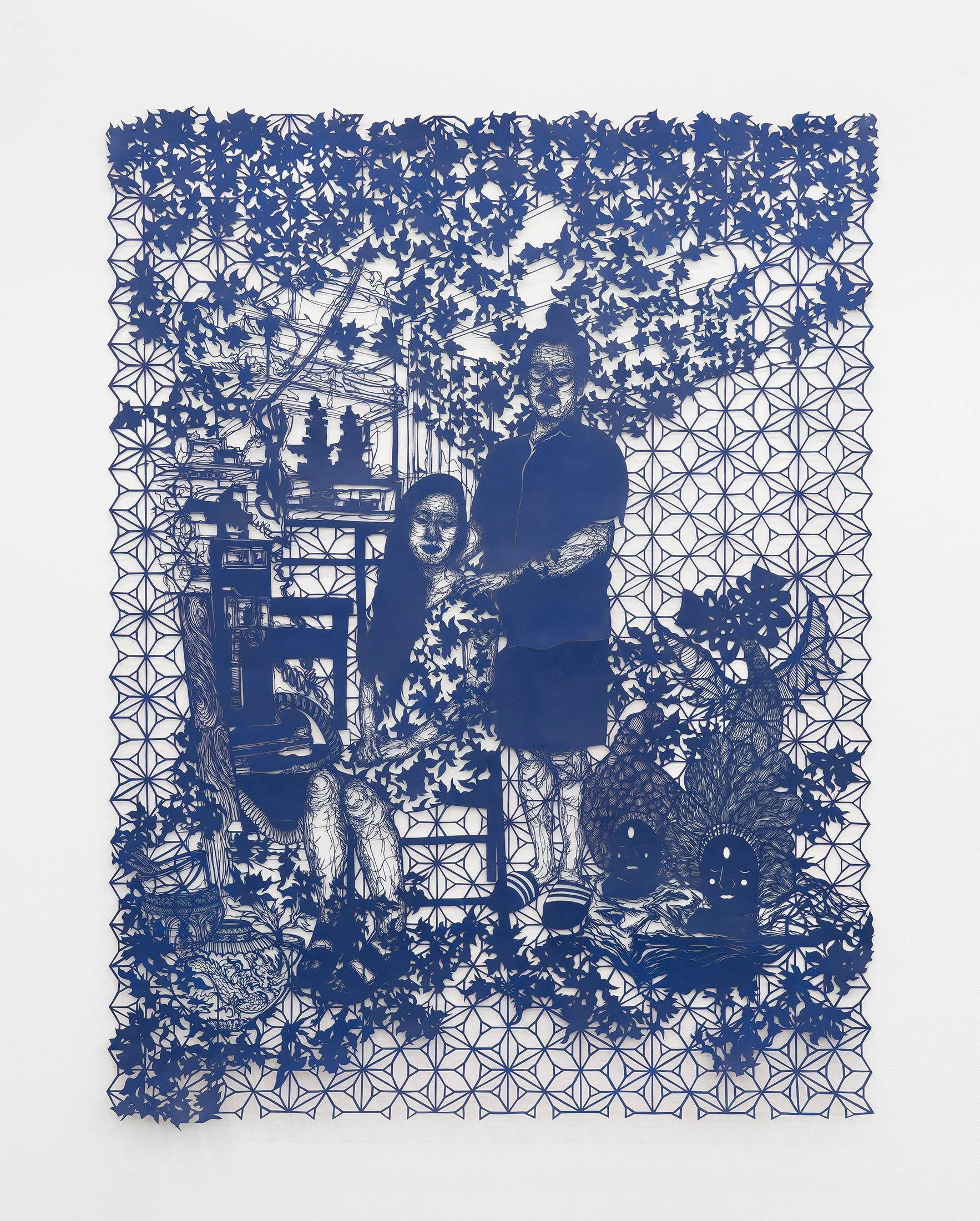

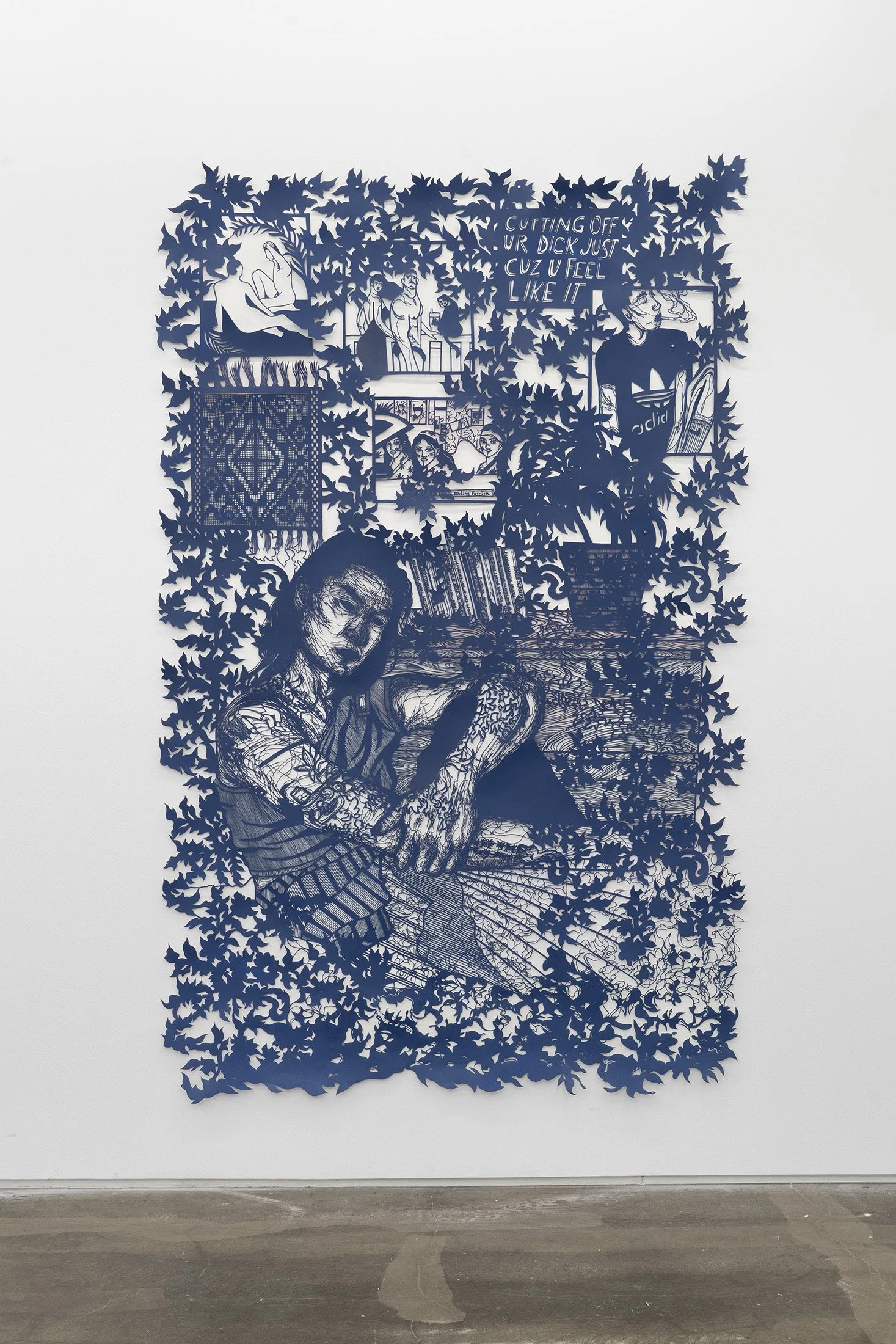

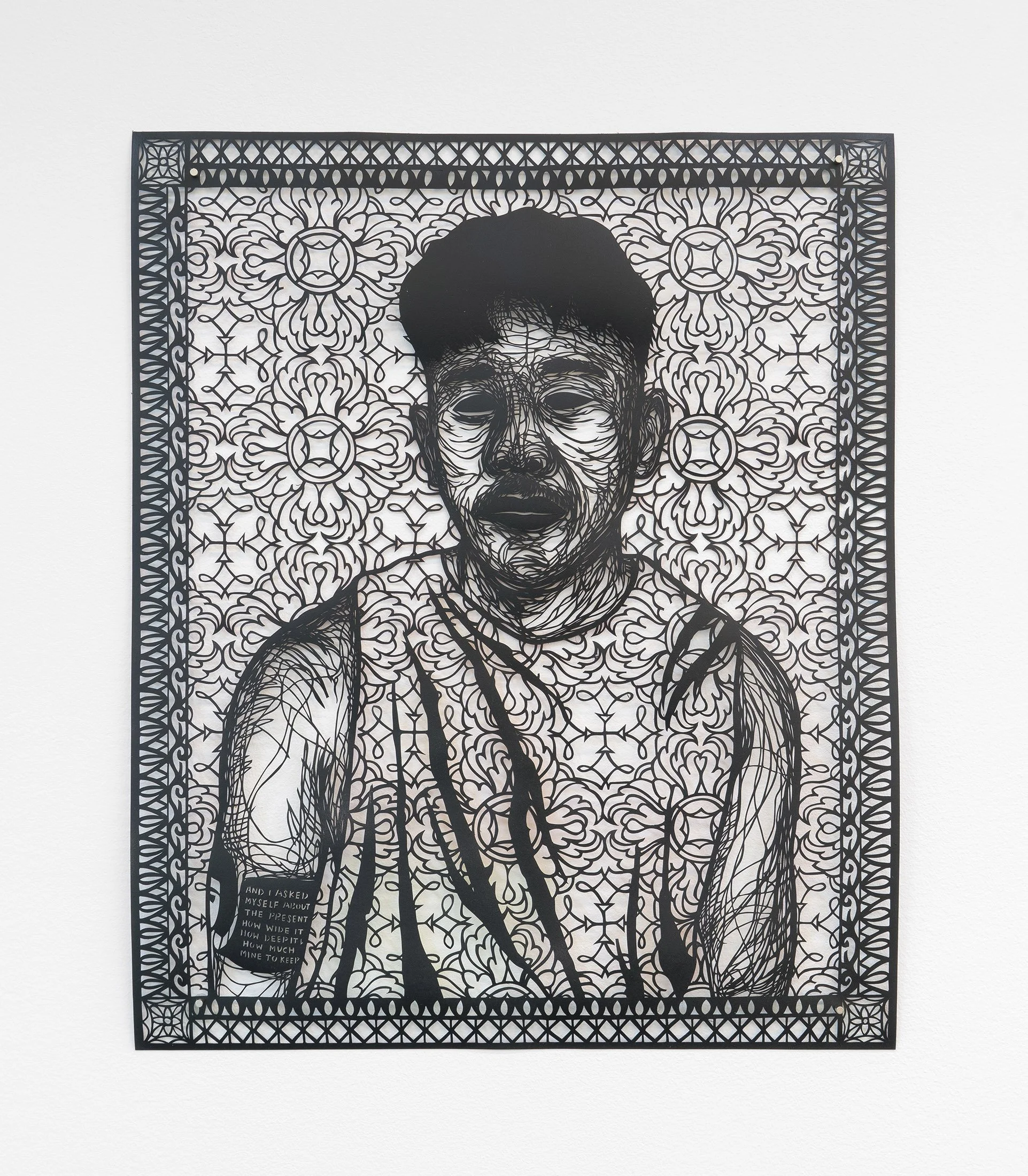

With an intuitive sense of beauty and precision in practice, the exhibition offers the artist’s new series of hand-cut works on paper, portraits of individuals and artifacts that have shaped Bui’s exploration into their Vietnamese heritage, the poetics of queerness, gender fluidity, the politics of identity, and reshaping silence. Their works are a panorama of metamorphosis, portraits that bear witness to whole beings in their myriad complexities which are carved in precious detail to communicate each person’s unique journey of breaking and becoming—rejecting stereotypes, shame, and internalized racism experienced by the AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) community by depicting scenes of intimacy, sexuality, and emotional release with nuance, sanctuary, and, in moments, ecstatic eruption.

Between both galleries, Bui interlaces personal subjects with archival objects, featuring images of friends, relatives, artists, porn stars, historic figures, and deceased creatives. Among these portraits are Nicholas Oh and Ayoung Yu, artists Bui has collaborated with for many performances, and Anthony Veasna So, the queer Cambodian American writer—individuals who provide Bui with a sense of possibility and guide them towards future understandings of themself. Other works present images of exploded vessels, fragments of ceramic vases from Asian art collections that Bui activates to confront Western institution’s historic practice of siloing Southeast Asian cultural narratives by emphasizing porcelain, resulting in an overgeneralized Orientalist perspective of the past. Further contending with the history of Orientalism, a series of new works explores Asian American masculinity and sexual representation with an examination of gay male pornography. Challenging the role the pleasure of porn plays in securing a consensus about race and desirability, Bui renders the association of bottomhood with Asian submission, abjection and anonymity. By depicting pornographic depictions of Asian men, Bui highlights and reclaims the mainstream media portrayal of Asian men as effeminate and asexual, restoring their power and autonomy by rendering them breaking through traditional vessels and shattering stereotypes. Bui shatters these vessels and subjects and reassembles them, tapping into the messiness, tensions, and trappings of visibility. In homage to each subject, Bui likens the hand-cut works to Joss paper: a ceremonial parchment burned as an ancestral offering in pan-Asian culture. To them, the act of burning symbolizes “the delicate dance between negative and positive space, presence and absence, and how so much of our formulation is through what we reject or take away.” Instead, they propose “purging societal projections of who we should be, burning away expectations, unlearning our ideas of gender and sexuality.”

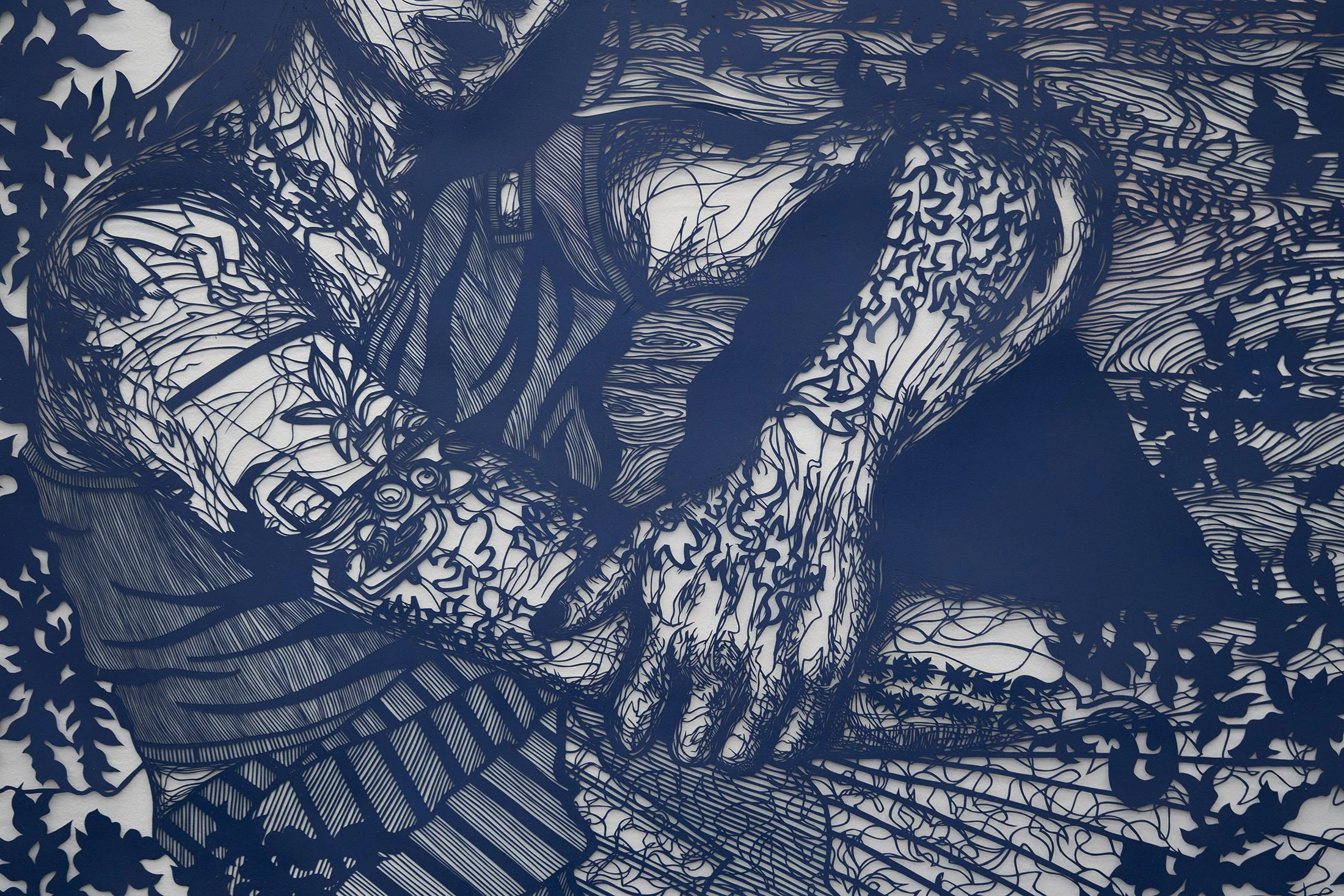

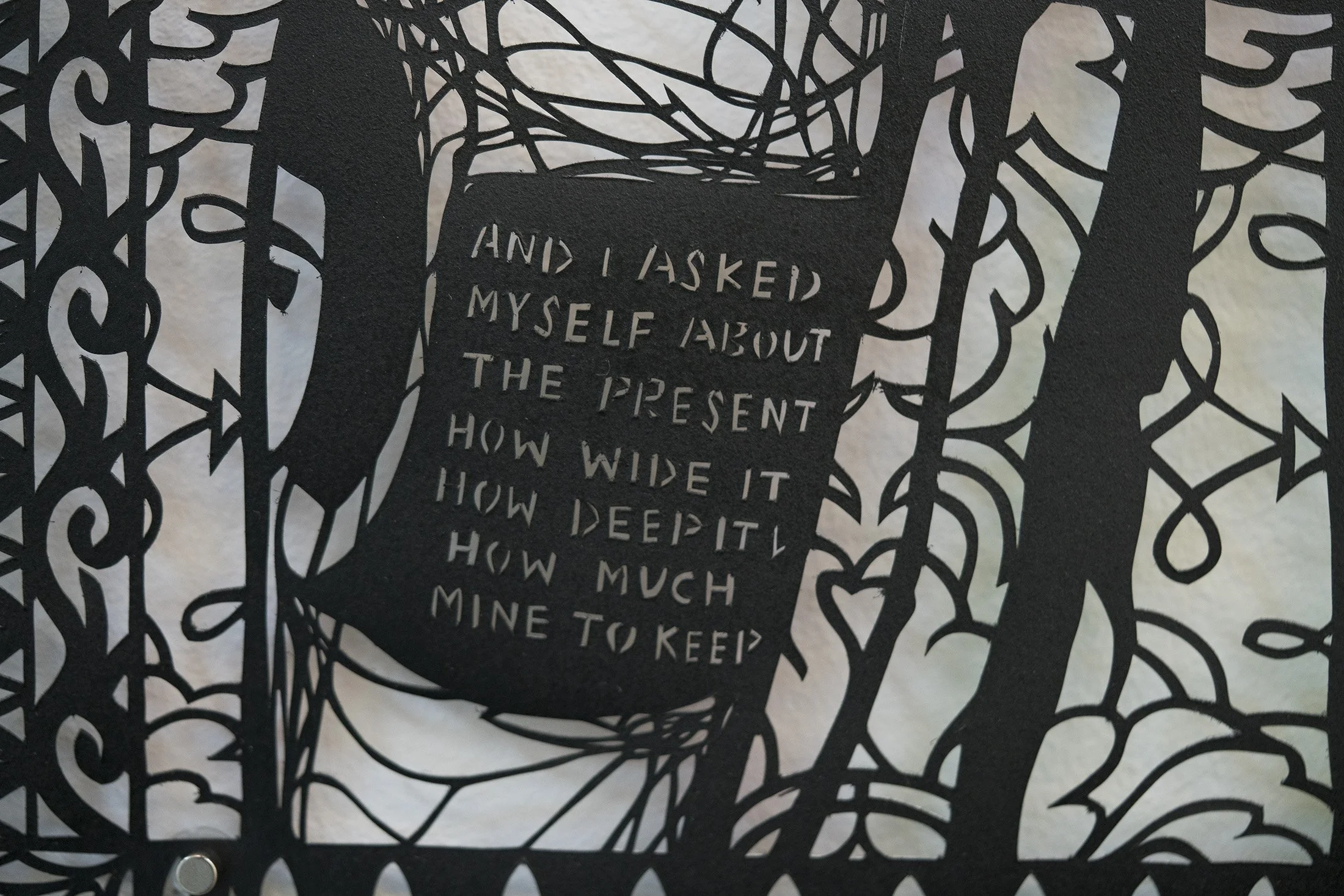

Bui creates each work from a single sheet of paper. First, with their instinctive hand, they render a composition on the page’s verso in colored pencil and marker. When the drawing is finished, the surface reveals a cartography of patterns, outlines, and silhouettes which they then incise with a scalpel until the image is revealed on the paper’s front side. With each work, the process of cutting is a means of engaging with their subject, the technical demands of the work offering them deep time to reflect on their relationships—presently or posthumously—and emulate intricacies of their kaleidoscopic lives. Each muse is settled in an interior space such as their home or studio, or an imagined landscape that incorporates details from their upbringing and heritage with natural elements—a garden of Eden of their own creation. Once the cut-out is complete, they glaze the paper with black, red, or blue paint, a palette that encourages the works to stand out from the wall and cast a phantasmagoric shadow. While Bui’s first solo show featured untreated paper, this series plays with symbolic connections to color, such as blue painted porcelain or traditional red paper cut-outs displayed for good luck during Lunar New Year. Ambitious in their scale, these works physically and conceptually hold space, portraying Bui’s monumental subjects in all of their divinity—a latticework of queer representation that celebrates their loved ones as they evolve over the course of their lives.

The exhibition is named after a verse from Franny Choi’s poem Orientalism Part I which reads: "There are many ways to hold water / without being called a vase. / To drink all the history / until it is your only song.” In their family’s native Vietnamese, the word nước is a homonym meaning both water and country. Honoring the term’s fluidity, Bui considers how water, and by extension the ocean, is a vessel of human movement for diasporas, migrants, and refugees, referencing their own family separating from their motherland and coming to call a new country home. Like precious fragments from a shipwreck, Bui is interested in the beauty and suffering which inform a multi-conscious existence, aspiring to find a more honest dynamic between interiority and exteriority—releasing a burst of joy from the sum of their parts.

Documentation by Robert Chase Heishman.